Foundation and first era (1771-1814)

The history of the National Museum of Natural Science started in October 17th, 1771, when the King Charles III founded the Royal Cabinet of Natural History advised by relevant members of his court. It was an institution dedicated to the dissemination and development of natural history in Spain that sought to rival the cabinets of curiosities, which were very popular in 18th century enlightened Europe.

The foundational collection of this Royal Cabinet came from a natural and artisitc heritage treasured by Pedro Franco Dávila, a rich Creole merchant born in Guayaquil (now Ecuador) and based in Paris. It took him 25 years to collect it and he donated it to the Spanish Crown in exchange for a lifetime directorship of the Cabinet.

Dávila was a big enthusiast of the natural sciences, especially interested in the mineralogy, malacology, certain groups of marine invertebrates such as corals and sponges, and also fossils. The publication of his work in three volumes are called Catalogue systématique et raisonné des curiosités de la nature et de l'art qui composent le Gabinet, in which he described his collection, built up and documented over a quarter of a century, opened the doors of the most prestigious scientific societies of the time, both foreign and Spanish.

In addition to being an expert in the natural sciences, Dávila was a great connoisseur of ethnography and art. His collection included 300 ethnographic objects from America, Indonesia, the Far East and Turkey; 250 archaeological objects from Egypt, Etruria, Rome and the Orient; and between 12,000 and 13,000 artistic pieces, such as medals and engravings. It also owned 50 scientific instruments and 200 maps, and its library contained 421 titles in 1,234 volumes.

After evaluating various venues where Dávila's large and varied collection could be housed, the Palacio de Goyeneche on Calle de Alcalá in Madrid was chosen. Here it shared its location with the Real Academia de las tres Nobles Artes (now the Real Academia de las Bellas Artes de San Fernando). After two years of refurbishment work, the Academy was installed on the first floor and in the basements, while the Royal Cabinet occupied the first floor and the attics. The natural sciences and art were brought together in the same building, the front of which bore a stone inscription typical of the Enlightenment: CAROLVS III REX / NATURAM ET ARTEM SUB UNO TECTO / IN PUBLICAM VTILITATEM CONSOCIAVIT / ANNO MDCCLXXIV (King Charles III associated Nature and the Arts under the same roof for the public good).

Dávila's extensive collection had arrived from Paris on four journeys, one by land and three by sea. Once in Madrid, the 250 drawers in which it was transported were deposited in the Palacio del Buen Retiro, waiting to be placed when the new building was ready. As director, Dávila designed the rooms in which the pieces would be placed. He drew up a document detailing this spatial planning: two rooms for animals, another for minerals, one for plants and several more dedicated to artistic objects.

In addition, other rooms were to be provided for laboratories to prepare pieces, to cut and polish hard stones or to carry out dissections. Finally, the Cabinet should have a room for duplicates where pieces of which there was more than one specimen would be kept for exchange with other institutions.

This incipient institution was conceived not only as a museum for the exhibition of natural and artistic curiosities, but also as a centre for the study and dissemination of knowledge of natural history, thus contributing to the development of science in Spain.

It's opened its doors in November 4th, 1776. This date was chosen to coincide with the name day of the king who made this project possible. The public success was immediate and substantial. Visitors numbered in the thousands each day. It was necessary to bring a guard of six soldiers to hold back the flood of people crowding the entrance. It was open to anyone without any restriction. Decency in dress and good behaviour during the visit were all that was required. It constituted a a major cultural event in Madrid at the time.

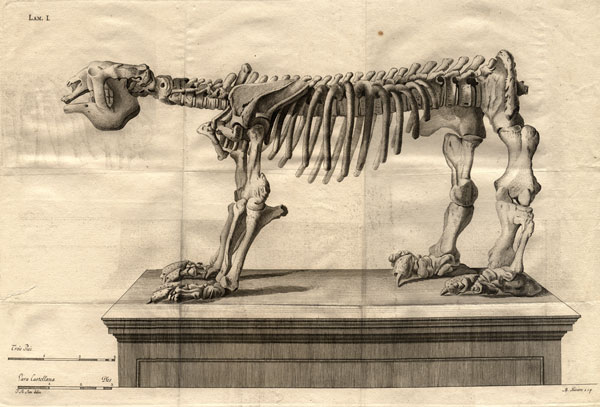

The monarchy support to this institution it became clear with the publication of a Royal Order in 1776. It ordered all the authorities of the empire, from viceroys to intendants, to send everything of natural interest found in their territories. Thanks to this Royal Order, it came to the Cabinet one of the most emblematic pieces, the megatherium, a full skeleton of an extinct giant sloth found on the banks of the Luján river, near Buenos Aires (Argentina). Drawings of this sample allowed Georges Cuvier of the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris to describe the species Megatherium americanum. Mounted in the petrifactions room of the Royal Cabinet, it was the first vertebrate fossil that was exposed to the public in Europe.

In 1777, it was designed as Deputy Director Eugenio Izquierdo, as secretary José Clavijo y Fajardo and as painter and designer Juan Bautista Bru. Despite of the help that the incorporation of these new positions represented, it soon proved to be insufficient. There was a great amount of work due to the continuous reception of shipments of natural and artistic pieces from Spain and abroad, especially from America. Material was also received from scientific expeditions (Alejandro Malaspina, 1754-1810), from exchanges with other institutions (Cabinet of Curiosities of the King of Denmark, the Imperial Cabinet of Vienna and the Royal Society of London) and from gifts from Charles III himself (the Dolphin Treasury, an Indian Elephant, an anteater or hard stone tables).

The purchase of pieces was another way in which the Royal Cabinet's collection was increased. For example, in 1785, by order of Charles III, the iconographic collection of the dutch painter Johannes Le Francq van Berkhey were acquired at public auction in Amsterdam. This had several thousand plates, most of them of natural history. Also, manufactures produced in the Far East reached Europe via the Manila Galleon route and the Royal Cabinet benefited from this, acquiring all kinds of art objects, especially from China.

All of this made possible that, in a little period of time, the space in the palace proved to be insufficient. To solve this problem, the construction of a new building designed by Juan de Villanueva was planned, although in the end it was used as a national art gallery (actual Prado Museum).

After Dávila's death in 1786, and after Nicolás de Vargas took up the post of interim director, Eugenio Izquierdo was appointed director and José Clavijo, deputy director. Eugenio Izquierdo's multiple occupations in the field of diplomacy and espionage for Charles IV's prime minister, Manuel Godoy, meant that Clavijo took over the directorship in practice until his departure from the Cabinet in 1802.

During Clavijo's management, important collections of Chilean minerals formed by the Heuland brothers, fish and marine animals from Cuba that he sent were incorporated, sent by Antonio Parra, o Paraguayan birds by Félix de Azara. The explorations in Spain in search of rocks and minerals by collaborators such as Francisco Javier Molina and William Bowles significantly increased the number of specimens in the Royal Cabinet's geological collection, particularly the pieces of crystallised sulphur from Conil (Cadiz). For his parte, Cristóbal Vilella y Amengual contributed marine specimens from Mallorca for twenty years.

Due to the War of Independence (1808-1814), the Cabinet closed its doors to the public, the teaching work of its School of Mineralogy was interrupted and its Annuals of Natural History ceased to be published. The revision of scientific works, support for expeditions and the cataloguing of its collections were also discontinued.

The Cabinet was looted by Napoleon's troops, although most of what was stolen was recovered after being reclaimed by the Spanish State. Among the items returned was the Treasure of the Dauphin, a collection of objects and precious stones that King Charles III himself had donated to the Royal Cabinet before it was opened to the public. It is now in the Prado Museum, having been incorporated into the collection in 1839.

In addition to numerous biological and geological specimens from this early period, the collections of the National Museum of Natural Sciences include valuable furniture, including the Manila table used by Dávila, as well as a bookcase and a clock made in Floridablanca's time. Also, there can be admired paintings like La Osa Hormiguera de su Majestad (1776) or the Quadro de la Historia Natural, Civil y Geográfica del Reyno del Perú (1799).

Text of Carolina Martín Albaladejo and Ana García Herranz